The 1619 Project Debate as a Lens for Teaching Historical Methodology and Historiography

The ongoing debate over The 1619 Project affords the opportunity for teachers to “teach the controversies” — to let students in behind the scenes to see how historical scholarship and criticism work.

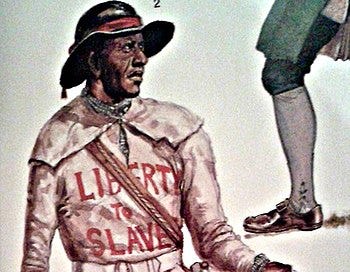

It has now been four years since journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones launched The 1619 Project in The New York Times Magazine, August 14, 2019 edition. The project takes its name from the pivotal year when the first enslaved Africans were forcibly brought to the shores of colonial America. Through a series of essays, articles, and visual storytelling, the project highlights the ways in which slavery and its aftermath have shaped the nation's institutions, policies, and racial dynamics.

Criticism of the work soon followed. In a December 2019 letter published in The New York Times, historians Sean Wilentz, Gordon S. Wood, James McPherson, Victoria Bynum, and James Oakes claimed the work has significant factual errors and misrepresentations of history. (You can read their critique and response from the Times Editor-in-Chief here). Other historians, including Woody Holton, have defended some of the specific claims regarding the influence of slavery on the coming of the American Revolution. Holton and Wood debated the topic in October 2021. Without naming the work directly, Wood also challenged these claims about slavery and the American Revolution in his 2021 book, Power and Liberty. Hannah-Jones provided additional support for her claims–citing Holton and other historians–in the book version of The 1619 Project, published in November 2021.

If all of this seems like old news, the The 1619 Project appeared again in historians’ discourse in summer 2023. In Johann Neem’s review of Myth America in The Hedgehog Review, he criticizes the American Historical Review December 2022 issue forum for presenting only a few “truly critical assessments” of The 1619 Project.

The ongoing debate over The 1619 Project affords the opportunity for teachers to “teach the controversies” — to let students in behind the scenes to see how historical scholarship and criticism work. Without commenting on the merits of any claims or positions, I offer some discussion points below on how this debate can be used as a lens for studying historical methodology and historiography.

Gatekeepers and Canons

Some historians seem to claim for themselves a role as gatekeepers of early American history. They argue that they should have been consulted as experts for The 1619 Project. Should history have gatekeepers?

The Times editor cites other scholars who were consulted. Who qualifies as an expert on a given topic?

Should we always consult a particular canon of historical works on a given topic? Does having a canon limit our ability to see new perspectives?

Facts and Interpretations

Some historians claim there are factual errors in The 1619 Project that need to be corrected. The Times editor argues that the disagreements are matters of interpretation, not facts. Can we draw clear distinctions between historical facts and interpretations?

Are claims about causation claims of fact or interpretation?

Do you agree with R.G. Collingwood’s claim, “For the historian there is no difference between discovering what happened and discovering why it happened”?

What kind of evidence and reasoning are needed to support claims of causation?

What are some of the common fallacies in historical analysis of causation? (See David Hackett Fischer, Historians’ Fallacies, Chapter 6). Do any of the causal claims of The 1619 Project or its critics commit these fallacies?

Debating and Debunking Narratives

Can history have multiple cogent competing narratives? (critical pluralism)

What makes some narratives more cogent than others?

How do we determine if a critique has debunked a myth or simply offered another cogent competing narrative?

If a particular narrative presents only a piece of a bigger picture, should it be disregarded, or instead paired with other narratives that present additional pieces?

Theory and Method

The 1619 Project uses Critical Race Theory as its overarching interpretative lens. What are the benefits of using theories in history? What are the challenges/limitations of theories?

What is the relationship between theory and method?

Historian Carl Trueman writes, “theory should be held loosely, as a hypothesis, and subject always to correction in light of the standard procedures of the historical profession. . . Historical explanatory schemes

should be heuristic not perspective.” (Histories and Fallacies, p. 73). How does Trueman’s statement help us evaluate the use of theories in history study?